The popularity of the franchise in the West today makes it seem as if "giant transforming robot-vehicles" have been around Western media and playroom chests forever. And yet there was a time no American boy had ever seen a car magically transform into a fighter robot. There's simply a before and after that first episode of the G1 Transformers animation, the first Transformers comic books and the first Transformers toys, and it took a cultural migration to get to where we are today.

article

The Transformers' Japanese origins

More than meets the eye, indeed.

Arjan Terpstra

22 Nov 2022 ⋅ 6 min read

The popularity of the franchise in the West today makes it seem as if "giant transforming robot-vehicles" have been around Western media and playroom chests forever. And yet there was a time no American boy had ever seen a car magically transform into a fighter robot. There's simply a before and after that first episode of the G1 Transformers animation, the first Transformers comic books and the first Transformers toys, and it took a cultural migration to get to where we are today.

Robots in disguise

Before Transformers hit in the US in the mid 1980s, a kid's headspace was filled with G.I. Joe, He-Man and Star Wars action figures, and Barbie, My Little Pony and Garbage Patch Kids dolls. Cute humanoid and animal characters were the toy and media trend for minors, generally speaking, not metallic hardware. Almost overnight, this changed when toy company Hasbro unleashed the Transformers onto the US markets. The robots in disguise captured the imagination big time, and made Hasbro the entertainment powerhouse it is today.

But where did these shiny and impressive robots come from? Culturally speaking, the US at the time had no history that explained this new mass phenomenon. There was no previous fighter robot trend to speak of, as robot love focussed on the humanoid characters in Star Wars and other Western sci-fi. And although a large American car culture existed, in toys and entertainment media, you could not discern any inclination among American youth to radically alter the shapes of their precious Matchbox and Hot Wheels toys.

Immigrants

The cultural pedigree of the Transformers lay elsewhere. Like many other things America made great, the idea behind the robots in disguise was imported, making the Transformers essentially immigrants. It's an American entertainment franchise grafted onto a pop-cultural trend that happened thousands of miles away, in Japan, where at the start of the 1980s robot entertainment was standard fare on TV-screens and on the pages of manga books.

Contrary to the US and other Western countries, Japan had a longstanding love-affair with robotic characters, dating back to tea-serving automata in the sixteenth Century. Various robot trends (in Japanese theater and other entertainments) culminated in the 20th Century. Especially after the Second World War, "super robot" stories were all the craze, inundating Japanese manga (comics) publications and anime (animation series). They featured robots the size of a building, with the fighting skills of a ninja or samurai—the "Seven Story Samurai trend" was huge.

Mobile Suit Gundam

In most of the stories' designs, the super robots visually leaned towards realism. From early examples like Tetsujin 28-go (also known as Gigantor in some regions) and Mazinger Z, to the massively popular military fiction series Mobile Suit Gundam, the robots looked futuristic, but it was a futurism that kept in line with what people expected to be realistic developments in military and space exploration hardware. As fiction, the super robot stories of course had many made-up details (like Mazinger Z's famous magical metallic alloy, called Chogokin), but otherwise the designs were rooted in science and technology.

Poster for the original The Transformers cartoon, by artist G.M. Eggleston, showing characters like Optimus Prime, Ravage, Starscream, Laserbeak and Soundwave. The art is available as museum-grade art print on this website. Click here for details.

Diaclone Car Robots

For the Macross series, Kawamori designed "mecha" that could change between human-piloted aircraft and robotic forms. This caught the attention of toy company Takara, who hired Kawamori to build a toy line of realistic earth vehicles (and also realistic looking items like cassette tapes or radios) that could transform into robot warriors.

As a backstory to what would be called the "Diaclone Car Robots" toy line, Kawamori envisioned a world in which humans defended Earth against intruders, hiding their mecha weaponry in plain sight by disguising them as cars, airplanes and other human vehicles. As was wont in popular robot fiction, the vehicles were piloted by humans—the toys had small seats built into the models to suggest as much, and came with "microman" figurines.

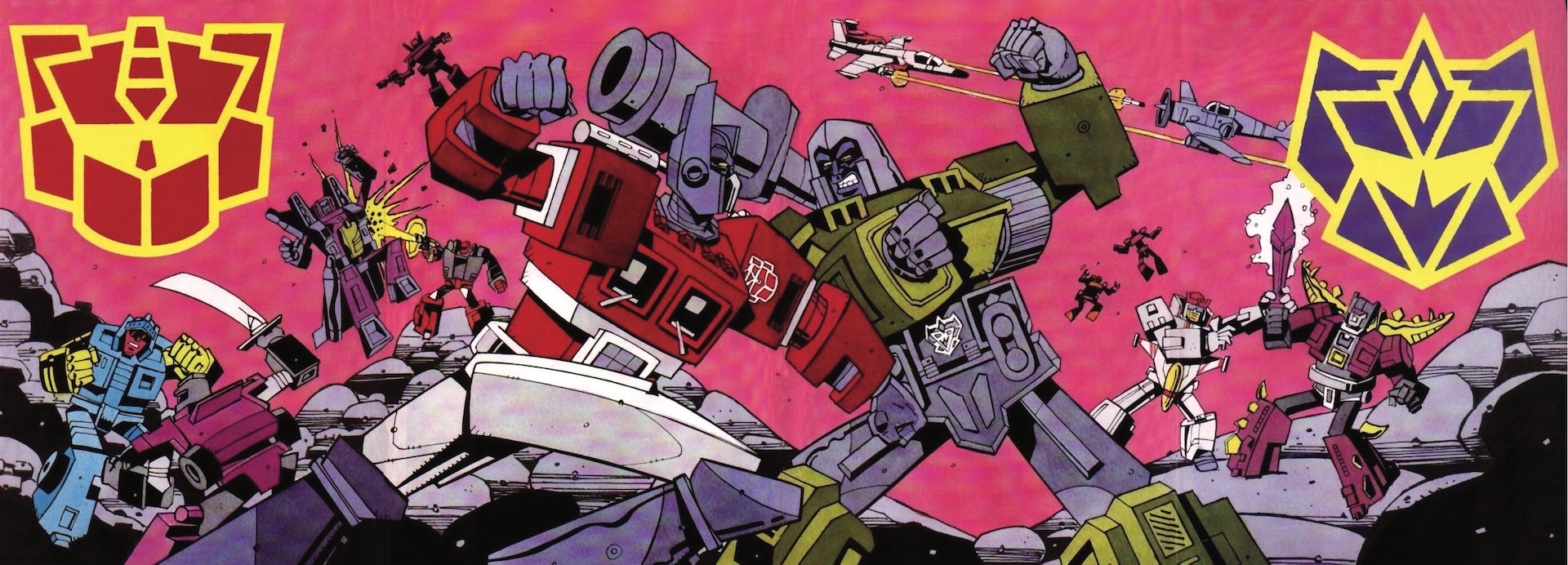

Gatefold poster, part of The Transformers: Generation 2 comics by British publisher Fleetway, #1. The four page , found in the central pages of the comic, has Optimus Prime and Megatron at each other's throats, with other Autobots and Decepticons assisting. Available as fine art print through this website. Click here for details.

Backstory

On the Japanese home market, the shape-shifting robot toys proved hugely successful, but Takara could not make the jump to the lucrative United States' markets—the rechristened "Diakron" and "Kronoform" toy lines were a dud, commercially. At this point, Hasbro stepped in. The US company had partnered with Takara before, and saw opportunities in the Diaclone toy line, if the backstory was altered to cater more to American tastes.

For the new toys, Hasbro hired Marvel Comics writer Jim Shooter, who famously wrote a new eight-page treatise that had nothing to do with Kawamori's earlier ideas. Shooter and others established a backstory we all now today, one in which Autobot robots hid on Earth, disguised as common vehicles, awaiting an attack by equally disguised Decepticons. In a significant departure from the Japanese backstory, both parties were depicted as sentient aliens. Out were the human pilots, and also the Microman figurines.

Legacy

The rest is Transformers history. A history that is definitely an American history, defined by the workings of American mass media and commercial enterprise. And yet the Japanese origins are still a huge part of the story. The Transformers' visual designs stayed close to the "realistic futurism" first established in Japanese culture, and pay visual homage to the "seven story samurai" ideas of large robots with advanced fighting skills.

On a smaller scale (literally speaking), collectors of the first batch of 28 G1 Transformers toys will notice the tiny seats in and on the Optimus Prime and Starscream models, and also on Dinobots and Insecticons in later toy lines. These details are the lasting legacy of the Japanese Diaclone toys: Hasbro used the exact same toy molds that were used in Japan, thus including the seats used for the Japanese micromen. Also superfans will know the popular Jetfire Autobot Air Guardian is an exact copy of Macross' VF-15 Valkyrie—a Macross model Kawamori had designed, and which Takara simply rebranded as a Transformer toy.

More than meets the eye, indeed.

The art was originally released as promotional art for War for Cybertron: Siege, with a line-up of Decepticons featuring Megatron, Shockwave, Soundwave, Laserbeak, Ravage, Starscream, and Thundercracker. Available as fine art print through this website. Click here for details.