Today, Terada enjoys freeform live drawing events, in the fashion popularized by his Korean counterpart Kim Jung Gi, where you sketch large and detailed images without drafting anything. Besides this, he has solo exhibitions of his large fantasy drawings (more about this later) and publishes art books by the dozen. Unsurprisingly, this prolific output has earned Terada the nickname, "King scribbler," or "RakugaKing", a riff on the Japanese word rakugaki: to scribble or doodle.

article

Artist spotlight: Katsuya Terada

Meet the "King scribbler" responsible for the looks of Zelda, Virtua Fighter 2, and much more.

Arjan Terpstra

23 Mar 2022 ⋅ 8 min read

Few artists are as prolific in their output as Katsuya Terada. The Japanese illustrator worked in every field from advertising to book illustration, and from manga to video games, leaving his mark wherever his strong lines and lively imagination took him. You find his name in movie credits, as a high-profile character designer for movies like Hellboy (2004), Blood: The Last Vampire (2009), or Godzilla: Final Wars (2004). He also has credit lines in large Japanese television productions like Yatterman and Kamen Rider, but your next online click may just as well unearth his Magic: the Gathering card designs, or Terada-drawn manga so obscure even a Japanese otaku needs a moment to interpret what it is.

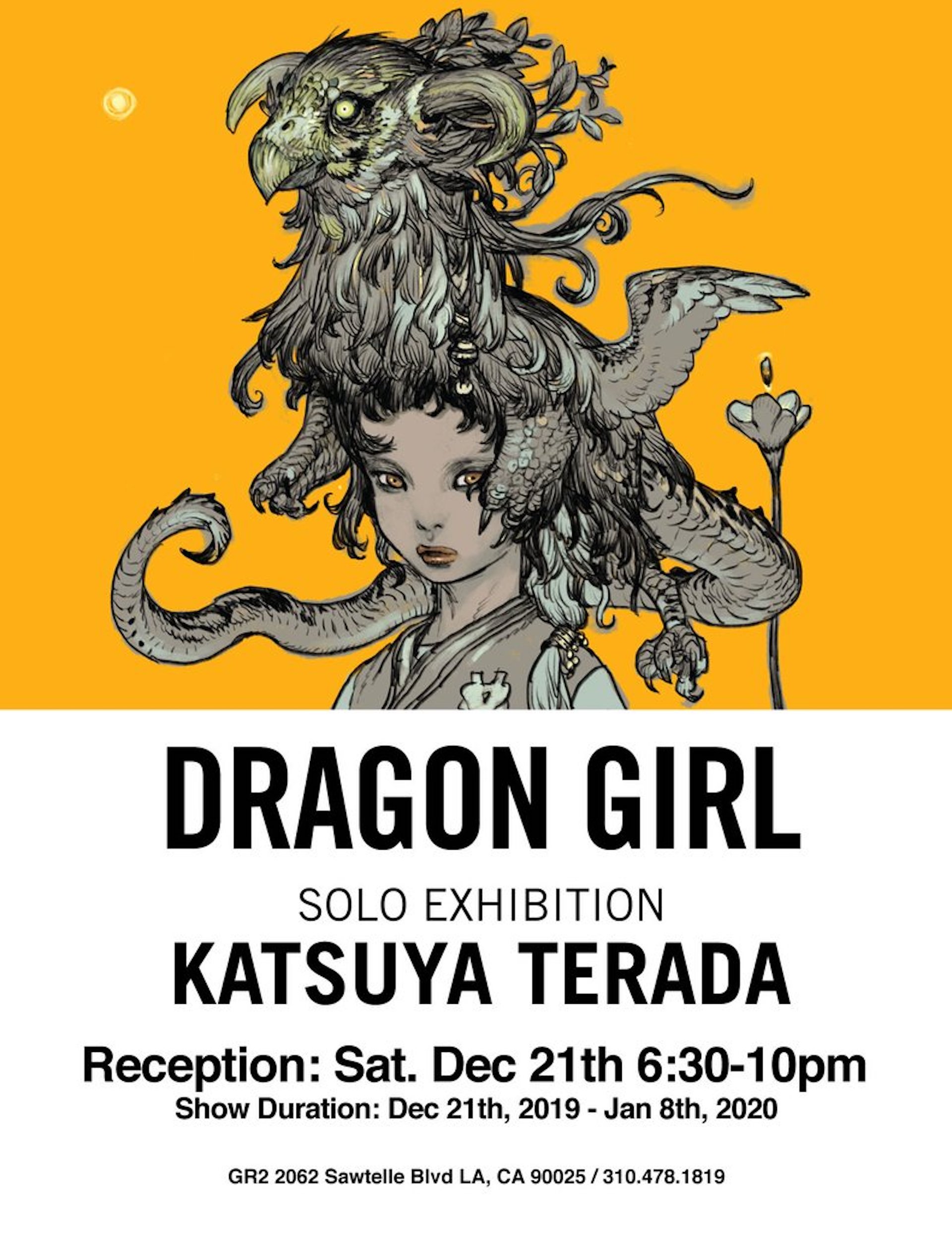

Today, Terada enjoys freeform live drawing events, in the fashion popularized by his Korean counterpart Kim Jung Gi, where you sketch large and detailed images without drafting anything. Besides this, he has solo exhibitions of his large fantasy drawings (more about this later) and publishes art books by the dozen. Unsurprisingly, this prolific output has earned Terada the nickname, "King scribbler," or "RakugaKing", a riff on the Japanese word rakugaki: to scribble or doodle.

Today, Terada enjoys freeform live drawing events, in the fashion popularized by his Korean counterpart Kim Jung Gi, where you sketch large and detailed images without drafting anything. Besides this, he has solo exhibitions of his large fantasy drawings (more about this later) and publishes art books by the dozen. Unsurprisingly, this prolific output has earned Terada the nickname, "King scribbler," or "RakugaKing", a riff on the Japanese word rakugaki: to scribble or doodle.

An incessant scribbler

An apt name, as Terada doesn't like to define himself other than as a "rakugaki" artist—someone known for his endless scribbling, drawing anything anytime anywhere, without worrying too much about meaning. In various interviews, he declines to be determined as character designer, manga artist, book illustrator or other, even though he clearly worked in every one of these roles.

Yes, he knows these jobs inside and out, excels at them, but simply feels best doing things like he did them for as long as he can remember: he's the incessant scribbler riding the Tokyo subway, forever drawing in notebooks he buys "by the box." Drawing is almost a physical need to him, he said, comparing his daily routine to the preparations of a marathon runner. "The more time I spend on drawing, the closer I get to that line that I am imagining. Every day of practice prepares you better for that one moment."

Early days

Katsuya Terada was born on December 7th, 1963, in the city of Tamano, Okayama prefecture, Japan. In elementary school, he stood out for drawing and painting ("I was small and couldn't study, so I focussed more on painting," he said). Like every Japanese boy, he was into manga, buying Weekly Shonen Jump and other titles from his pocket money. He daydreams about being a cartoonist someday, but worried about having to write his own stories. In junior high school, he changed his mind and geared more towards being a book illustrator ("I wanted to have it the easy way. An illustrator doesn't have to think about the story.")

At age 15, he discovered the work of French cartoonist Moebius and of Katsuhiro Otomo, the writer of Akira. In Terada's mind, these artists combined the clean line art seen in book illustration with the dynamics of manga, opening up possibilities he did not see before. "Moebius was such an influence when I was a teenager, I'm kind of embarrassed by it now. You can really draw anything, if you apply Moebius' style. Because suddenly your manga character doesn't have to be as stylised (as was custom in manga at the time), but they can be much more realistic. In short, I found a lot of possibilities in Moebius' linework."

Switching gears

After high school, he enrolled in Asagaya College of Art and Design in Tokyo, a vocational school, and took on his first assignments, designing advertisements. This business quickly took off, leading Terada to rent his first apartment ("a four and a half tatami apartment" he explained to an interviewer, one small room measuring not more than 2,5x3 meters). Here, he would withdraw from his studies more and more, working on a discarded drafting desk he borrowed from school, the only other furniture a futon bed carried over from his parent's house.

His fortunes changed when, at age 21, he received a call from animator Toshio Nishiuchi, who asked Terada if he knew Nintendo's home entertainment system, the NES/Famicom. Nishiuchi had painted some concepts for an upcoming game called "Detective Jinguji Saburo Shinjuku Central Park Murder Case," but his designs were deemed a little too cute by the game's publisher, Data East. It fell to Terada to design something "more hard-boiled," doing the character designs, background illustrations, some art for the instruction manual, as well as the logo.

Drawing on Zelda

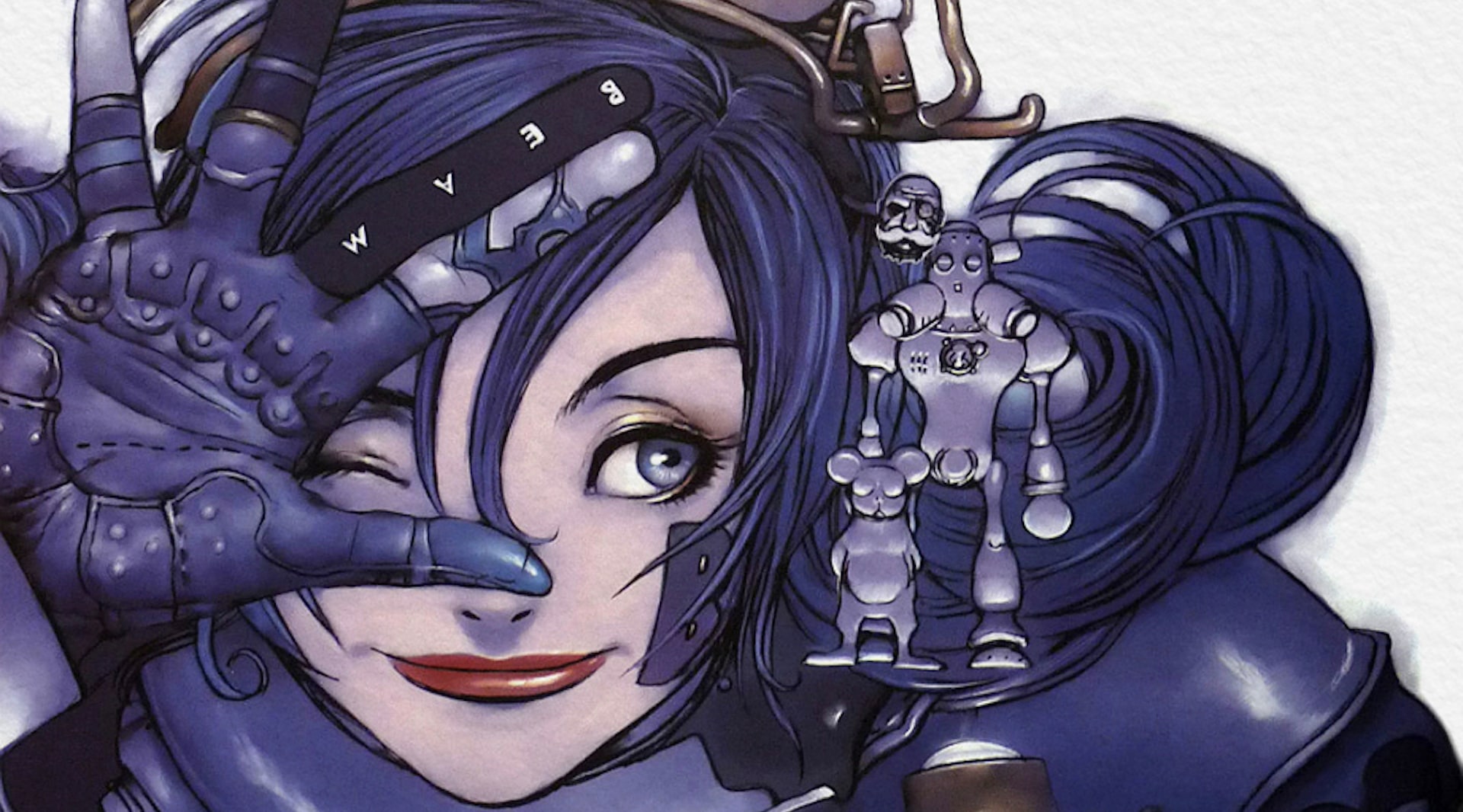

This assignment set Terada up for more work in the Japanese games industry, designing art for dozens of titles. Most of these were only published in Japan, but that did not mean Terada's work could not be found abroad. Between 1989 and 1995, he contributed to Nintendo Power, the promotional magazine for North American markets, where he drew a remarkable set of illustrations for The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening, and The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past. Another set of Link's Awakening art was exclusive to the official German-language player's guide. These printed Zelda illustrations stunned players with powerful imaginations of Link's adventures—as the NES had a limited capacity to show details on a screen, a player's guide filled in the visual gaps by showing more elaborate details.

Other high-profile video game gigs followed soon: the box art for the Japanese edition of Prince of Persia for the SNES is his, for instance. Around the same time, Terada was asked to develop the character designs for Virtua Fighter 2, SEGA's 1994 follow-up to the highly influential Virtua Fighter. Here, he helped the team embellish the roster of fighters, seeking an art style that embraced the realism of the 3D fighting game. "I felt this was an easy job to do," Terada said, but he became so enamored with it, he asked his production manager if he could have a cabinet installed in his apartment.

"I said I wanted it at all costs, and one fine day a small truck came to deliver one to my dilapidated apartment. But the entrance stairs were too narrow and I had to send it away. Later, I received a phone call to tell me that they would bring it to me by taking it apart this time. Afterwards, I started my days by plugging in the machine. However, the domestic electrical voltage was very low and it took about one hour for the machine to be fully running, haha."

Manga and other works

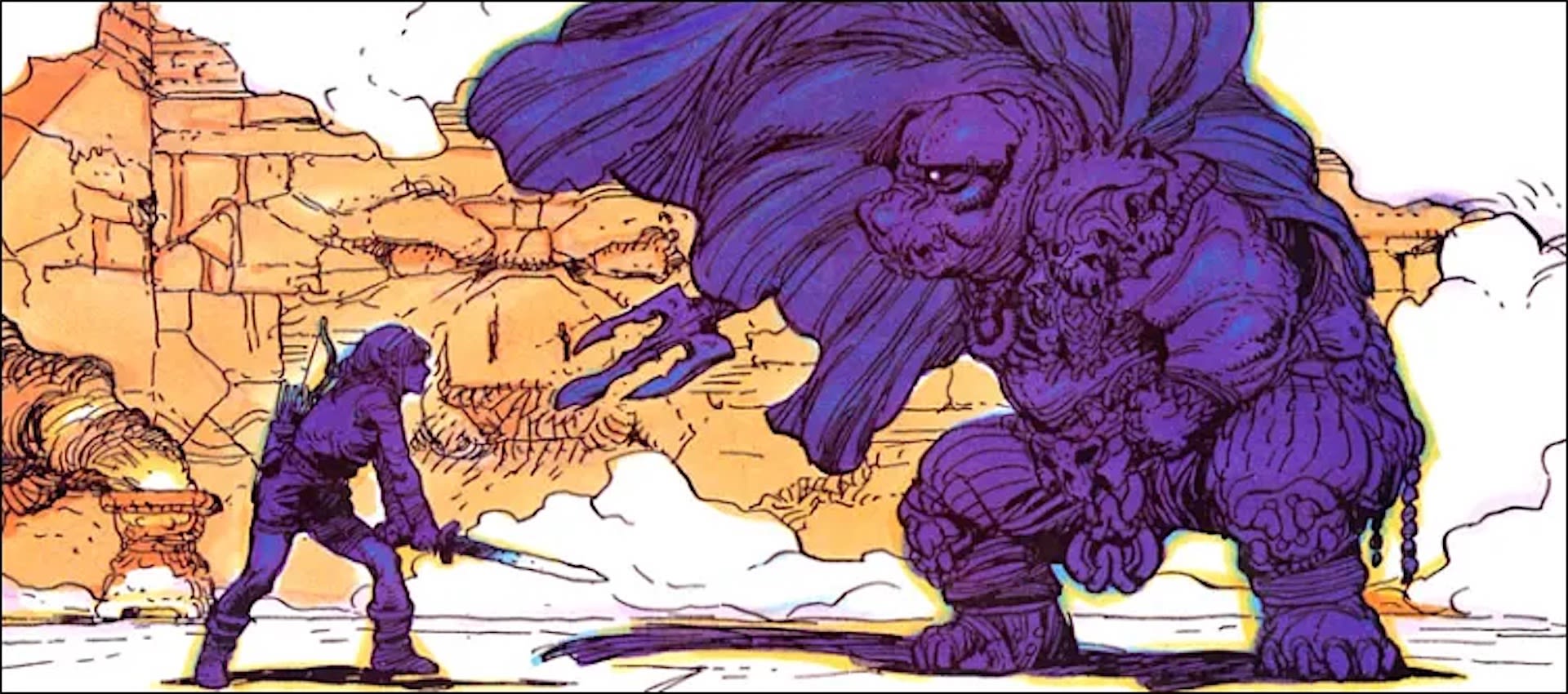

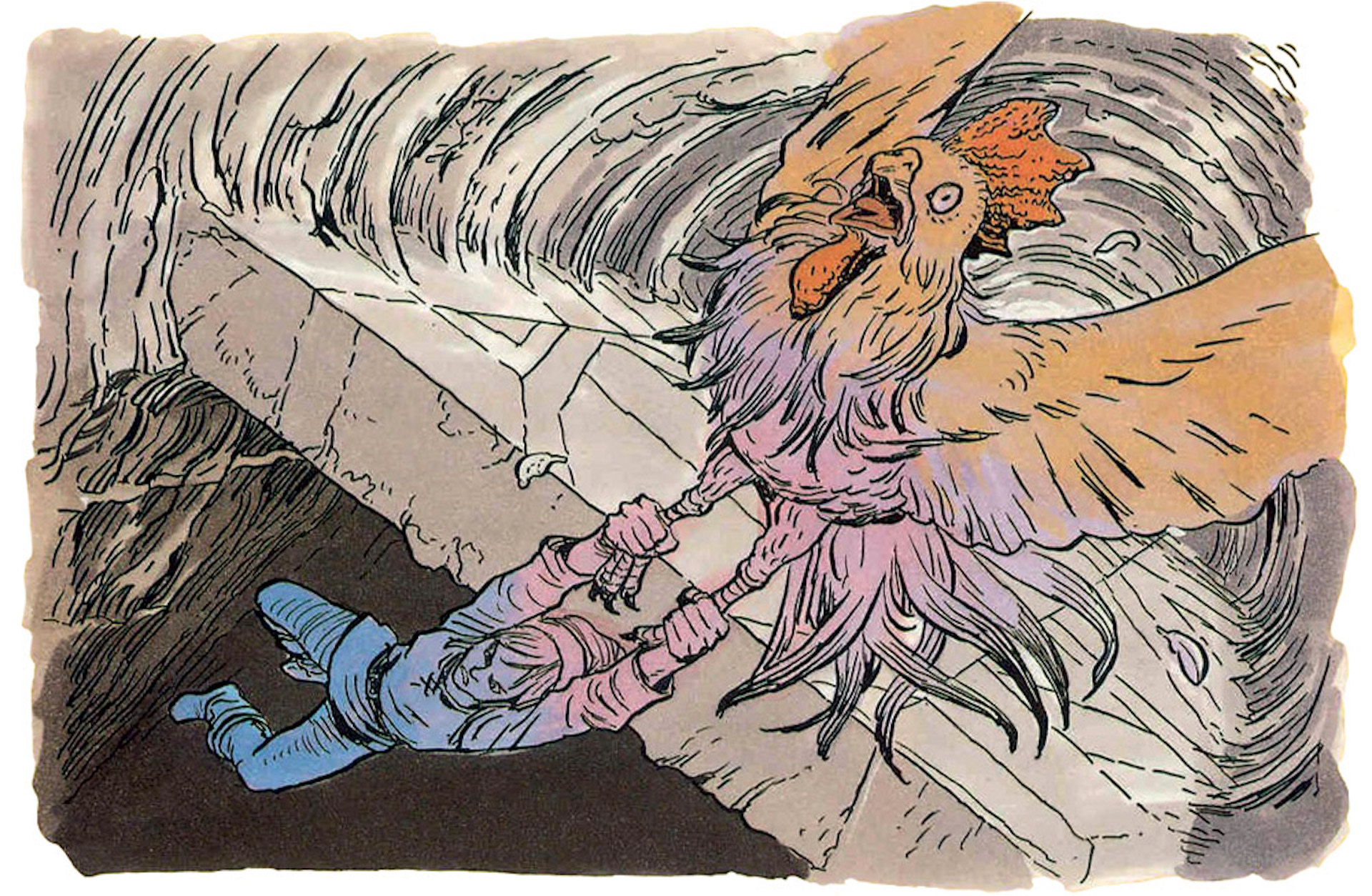

Terada's work greatly expanded on the back of these successes, making him one of the most wanted artists in Japan. It has led to great art, as is testified in The Monkey King I and II, two full-color manga books, written and drawn by Terada, who reinterprets a well-known epic of Goku, who escorts the monk Sanzo on a perilous journey across, as the flap text has it, "a wasteland filled with weird, violent, and sexy demons."

Terada's work on the Monkey King manga series is widely seen as among his finest work. As one reviewer put it: "His artwork--every page is painted-- explodes with energy, overflows with baroque lineation and voluptuous figuration, and exploits color like a chameleon with multiple personality disorder."

Weirdness is also a big factor in Terada's free work, an ever-expanding universe of inspired and intriguing characters drawn in an unique pictorial style that, after all these years, still owes a debt of gratitude to Moebius and Otomo: they're expressive, futuristic characters drawn in a realistic style, but are never set in a realistic world. And the more you look at these artworks, the more you realize they're scribbles, but on a large scale. It's line art, on large sizes, made by an incessant doodler.

This, he upholds, is what happens when you keep your sketching game up. "I have a habit of looking at objects and imagining how they would transfer from shapes to lines. Over time, I have built a visual library in my head where I am able to pull up these images and details when I need them."

This, he upholds, is what happens when you keep your sketching game up. "I have a habit of looking at objects and imagining how they would transfer from shapes to lines. Over time, I have built a visual library in my head where I am able to pull up these images and details when I need them."

Digital media

Importantly, these images need to come naturally. "I don't want to be a slave to the art, I don't observe scenery for the sake of observing. My initial desire is always to create a world I have never seen before." Over the years, he used various painting media such as water-based markers, paints, brush pens and pencils to reach this goal, before switching to digital media—today, nearly everything is sketched out on a 13" iPad. What he likes from digital media is both the sense of speed, and the freedom he has to draw things wherever he travels.

But to Terada, art is never about the medium, the canvas. "I wasn't interested in the filters that are unique to digital (work). It's important that the same picture can be created regardless of whether you draw in analog or digital media. When gadgets will be hard to use, I will go back to analog immediately. My right hand is my most reliable tool."