It comes as no surprise then, to see games and gaming catch the eye of museums and other places where societies reflect on past and present. A growing interest in the phenomenon already spawned spectacular exhibitions like the travelling Game On exhibition by the Barbican Centre (London, since 2002), The Art of Video Games by the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington, DC, 2012), Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt in the V&A (London, 2018), and many more. Also the MoMa in New York curates video games for its collection since 2012, and museums like the Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie in Paris, the ACMI in Melbourne, the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, New York, and the Computerspiele Museum in Berlin devote large portions of their space to video games.

article

The state of video game curation

What's going on in the world of video game exhibitions? Experts share their thoughts.

Arjan Terpstra

01 Feb 2022 ⋅ 9 min read

In 2021, video games reached a six-decade milestone, when the world celebrated the launch of Computer Space. Since that moment in the Fall of 1971, when games swapped academic research centres for bars and other social haunts for the first time, playing video games has bloomed into a massive social phenomenon and an economical and technological powerhouse, impacting our lives in a myriad of ways.

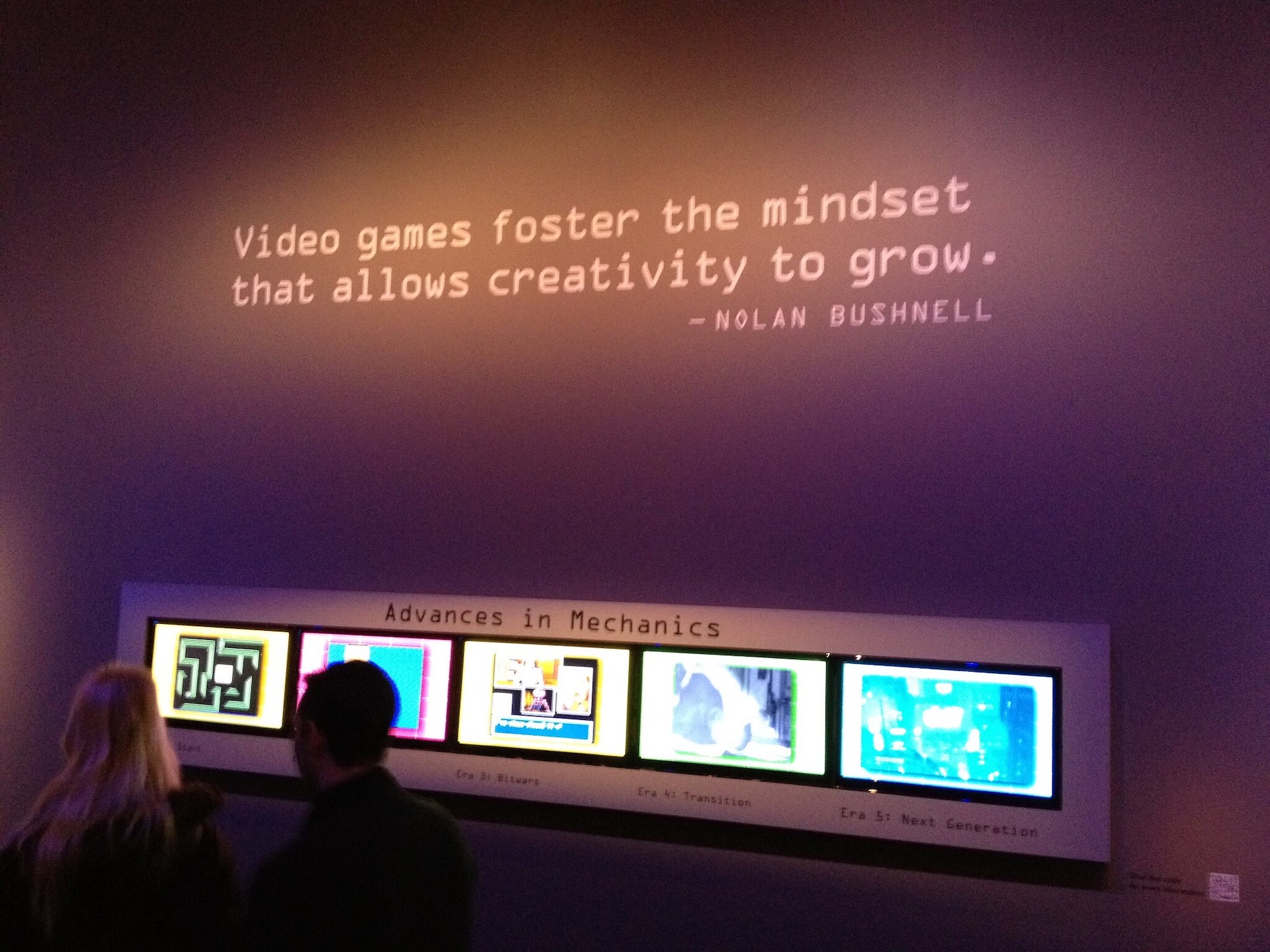

It comes as no surprise then, to see games and gaming catch the eye of museums and other places where societies reflect on past and present. A growing interest in the phenomenon already spawned spectacular exhibitions like the travelling Game On exhibition by the Barbican Centre (London, since 2002), The Art of Video Games by the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington, DC, 2012), Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt in the V&A (London, 2018), and many more. Also the MoMa in New York curates video games for its collection since 2012, and museums like the Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie in Paris, the ACMI in Melbourne, the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, New York, and the Computerspiele Museum in Berlin devote large portions of their space to video games.

It comes as no surprise then, to see games and gaming catch the eye of museums and other places where societies reflect on past and present. A growing interest in the phenomenon already spawned spectacular exhibitions like the travelling Game On exhibition by the Barbican Centre (London, since 2002), The Art of Video Games by the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington, DC, 2012), Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt in the V&A (London, 2018), and many more. Also the MoMa in New York curates video games for its collection since 2012, and museums like the Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie in Paris, the ACMI in Melbourne, the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, New York, and the Computerspiele Museum in Berlin devote large portions of their space to video games.

While the list is impressive, it is by no means exhaustive, as more exhibitions and museums devoted to games and gaming pop up everywhere. And while all share an obvious passion for the medium, the curatorial strategies are highly diverse, and range from the preservation of hard- and software to the exhibition of experimental video game art. Which begs the question: what, exactly, is the state of video game curation these days?

To find some answers, we talked to three top-level curators, experts involved in some of the largest video game exhibitions. Chris Melissinos was the guest curator for The Art of Video Games at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and Marie Foulston curated the spectacular Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt exhibition for the V&A in London, both in the capacity of specialist external curators. Patrick Moran works at the Barbican Centre, and oversees all travelling exhibitions, including Game On (the traveling show with hundreds of games playable on original hardware), and Virtual Realms: Videogames Transformed, among others. All were interviewed remotely, separate from each other, and speak on personal terms; their views don't represent the institutes they work or worked for.

Exhibition experts

To find some answers, we talked to three top-level curators, experts involved in some of the largest video game exhibitions. Chris Melissinos was the guest curator for The Art of Video Games at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and Marie Foulston curated the spectacular Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt exhibition for the V&A in London, both in the capacity of specialist external curators. Patrick Moran works at the Barbican Centre, and oversees all travelling exhibitions, including Game On (the traveling show with hundreds of games playable on original hardware), and Virtual Realms: Videogames Transformed, among others. All were interviewed remotely, separate from each other, and speak on personal terms; their views don't represent the institutes they work or worked for.

What's the state of game curation to them? "Video games are an undeniable part of contemporary culture. This offers a lot of opportunities for cultural institutes to engage with the medium and connect with new audiences", says Marie Foulston. Patrick Moran sees the same: a surge in attention for the medium at the level of cultural institutes. "In the UK at least, we see games being built more into institutions, as part of larger collections and shows. Also it's nice to see games discussed as part of different contexts: design, tech, social, historical, et cetera."

All agree video games are ubiquitous, and public interest is rising, also with non-gaming audiences. But that doesn't mean curators will engage with the medium, Chris Melissinos explains. "Of course it's great to see more and more happening. And yet bigger museums in the States often seem to have a desire to deepen the curation of video games, but have been slower to act upon long-form curation efforts. There are a number of smaller or industry focused institutions in the US, like the Strong Museum of Play (a collection-based, permanent museum on gaming in the broadest sense—AT), that are the exceptions to the rule in this respect."

Museum engagement

All agree video games are ubiquitous, and public interest is rising, also with non-gaming audiences. But that doesn't mean curators will engage with the medium, Chris Melissinos explains. "Of course it's great to see more and more happening. And yet bigger museums in the States often seem to have a desire to deepen the curation of video games, but have been slower to act upon long-form curation efforts. There are a number of smaller or industry focused institutions in the US, like the Strong Museum of Play (a collection-based, permanent museum on gaming in the broadest sense—AT), that are the exceptions to the rule in this respect."

Surprisingly, one of the challenges curators face in mounting a video game exhibition, is the games themselves. What games are, and how you exhibit them, can be hard to pin down, Melissinos says. "How do you build something that not only adheres to your curatorial sense of contextually relevant conversations, but also engages them in relevant ways? Video games demand our attention because, unlike a book or a movie, a video game story achieves the intent of its author through the playing of the game, while every player’s experience is more nuanced and personal. It's relatively easy to just build a retro arcade and have people enjoy themselves, yet as a curator your reflex is to help players understand the deeper meaning in those games, position them against what was going on in society when they were created, and how the art form has changed over time. It is a balancing act."

Marie Foulston remembers sitting down with the team for the Design/Play/Disrupt exhibition, with the same questions. "There are many different ways a video game can be perceived or defined. So as curators we need to ask what is the story we want to tell about this game, and then ask how we can best convey that? The theme for our exhibition was of transformation in the medium, each game that was exhibited was an example of makers pushing back against expectations of what games are."

Transformation

Marie Foulston remembers sitting down with the team for the Design/Play/Disrupt exhibition, with the same questions. "There are many different ways a video game can be perceived or defined. So as curators we need to ask what is the story we want to tell about this game, and then ask how we can best convey that? The theme for our exhibition was of transformation in the medium, each game that was exhibited was an example of makers pushing back against expectations of what games are."

"But selecting what games to include to some extent was the easy part, because then you bump into the realities and traditions that come with the established exhibition formats in many institutions. ‘Here's your allotment of square metres, X square metres means this many objects, this is how long we expect each person to spend looking at each object.' But video games are a performative, digital, ephemeral medium that often don’t conform to those display methods and nor should we limit them to them."

A lot comes down to finding the right curatorial language, Patrick Moran argues. "It's inevitable we will see an increasing richness in the kind of shows you can produce around games and gaming, which fits the current trend of museums diversifying their curatorial ideas. Museums are changing independent of games, focussing more on event programs and online interaction, to engage multiple audiences. The way forward for video game shows is finding different focus points for different groups of people. Unfortunately that's also a constant struggle curators are engaged in, as different groups tend to have very different expectations. A gamer may visit when you advertise playable video games, but regular visitors expect a "proper" exhibition, and you somehow have to square the two."

A lot comes down to finding the right curatorial language, Patrick Moran argues. "It's inevitable we will see an increasing richness in the kind of shows you can produce around games and gaming, which fits the current trend of museums diversifying their curatorial ideas. Museums are changing independent of games, focussing more on event programs and online interaction, to engage multiple audiences. The way forward for video game shows is finding different focus points for different groups of people. Unfortunately that's also a constant struggle curators are engaged in, as different groups tend to have very different expectations. A gamer may visit when you advertise playable video games, but regular visitors expect a "proper" exhibition, and you somehow have to square the two."

Games as art

Melissinos agrees. The Art of Videogames exhibition played into the age-old "are games art" debate, but was very careful not to alienate audiences. "Due to their nature, video games demand more of the viewer or player because their final expression occurs when they are engaged with a game, and that is a different experience for each player. While all creative works and expression is “art”, one has to be careful when a game is purposely described as an “art game”, which can diminish its value as either art or a game. Its designation or acceptance by the broader population as art is not entirely up to the artist themselves."

"Additionally, I believe that a purely academic approach to a game’s dissection sanitizes the game as a whole and it is easy to lose the human element on both sides of the screen. It is important that the visitors to such an exhibition not only learn a bit more about the game’s intention, but see and feel the reflection of their own experience with the games in the materials displayed.”

Going forward, what do the experts see happen in the future? What type of exhibitions will we see when Computer Space is seventy, eighty years old? Melissinos hopes we will be able to better harness the inherent qualities of "the most expansive art form we ever had at our disposal" in museum shows. "There's something bigger going on with games that just resonates deeply with players; it’s more than just the game itself. When people describe their favorite memories about playing, those memories go beyond the TV to include everything happening around them: who they played with, where they played, et cetera. Games simply provide a context to our lives in a way other media just can not match, and I hope we can bottle that magic a bit more in future exhibitions."

Future magic

Going forward, what do the experts see happen in the future? What type of exhibitions will we see when Computer Space is seventy, eighty years old? Melissinos hopes we will be able to better harness the inherent qualities of "the most expansive art form we ever had at our disposal" in museum shows. "There's something bigger going on with games that just resonates deeply with players; it’s more than just the game itself. When people describe their favorite memories about playing, those memories go beyond the TV to include everything happening around them: who they played with, where they played, et cetera. Games simply provide a context to our lives in a way other media just can not match, and I hope we can bottle that magic a bit more in future exhibitions."

"As a curator I’m interested in thinking of games as performance," Marie Foulston adds. "They're a time-based medium that's often at odds with how we think a museum should display works. For example, if the Bloodborne single-player experience is around 30+ hours, how can you exhibit that in a space people are expected to be in for maybe an hour or two at most? ! But, what if we didn’t limit ourselves that way? If we allow ourselves to break the mold of what a museum should be, so to speak, a lot more is possible in terms of experiences. What if we embraced the depth and endurance a 30 hour exhibition could offer? We should look towards escape rooms, theatre and performance art, or platforms like Twitch and allow ourselves to conceive of new hybrid experiences that challenge our expectations."

The Dutch Belvédère Museum (Heerenveen, the Netherlands) in its 2021 "Arranged Realism - Art in Games" exhibition, uniquely showcased three large sculptures used in the development of Dishonored games. Combined with Dishonored2 concept art on the wall behind the statues, it highlighted the aesthetics of the creative process.

Player history

Patrick Moran offers the same outlook: the way forward is in more experimental and diverse projects. "People want to be immersed in these game worlds, also in your exhibition, as every game highlights a particular moment in time for them. And while we know this, we don't seem to capture those moments well enough, I feel. How do you curate the craze about online FUT in FIFA, the online chatter about it, who played it, where, and when? This inevitably leads to questions about how we organise future exhibitions, and also about how to document gaming communities better as we're missing "the history of the player" at this point."

The other change Moran foresees is a bigger involvement of the large game studios of this world. "What we don't see today is big franchises organising their own shows, signature shows contextualising their games, showing things like the innovations within the franchise, its history. Think what it would mean to players if a studio would open up about Grand Theft Auto, or Super Mario, explaining the design processes behind the games, the lore, everything. We already see this trend with other pop culture—Star Wars, David Bowie, Bjørk, Alexander McQueen. Why not games?"