Emotions

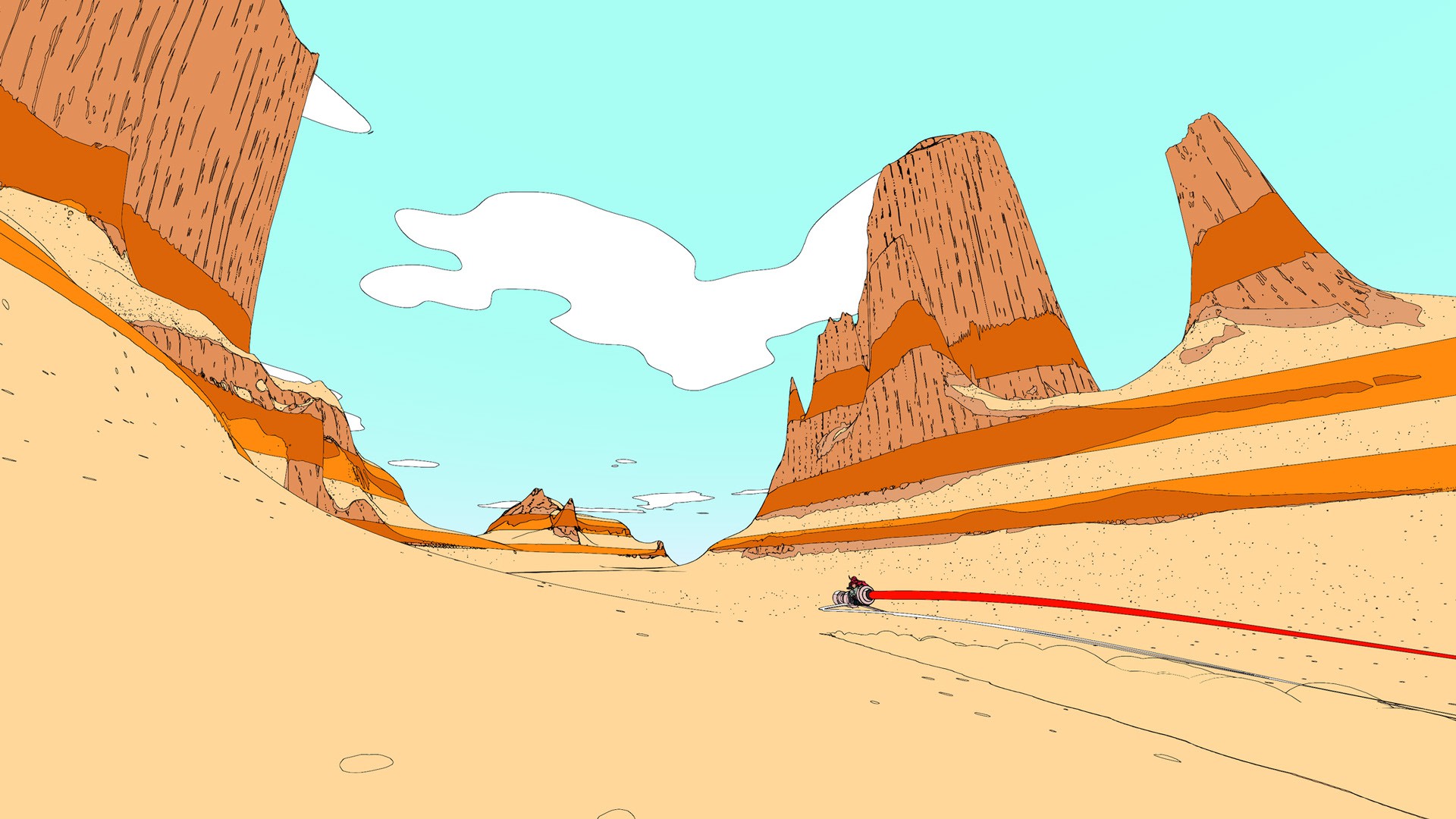

“The main emotions we focussed on in Sable are a sense of curiosity, wonder and existential loneliness”, says Kythreotis. “We really want people to be able to get lost in the world and the art is the most immediate way to captivate the player’s imagination”. For this, Shedworks - a two-men operation based in a literal garden shed in North-London - developed a simple style with sparse details. Kythreotis: “Sable is all about finding places the player hasn’t explored yet, people they are yet to meet or cultures and history they haven’t encountered. The overall aesthetic is geared towards this: it reflects the relative emptiness of the desert, with some of the details - the landmarks important for orienting yourself - really standing out on purpose.”

Finding this simple style - and one this stunningly original in a video game - took a long time. The gestation of the idea that would finally become the Sable concept, is measured in years rather than months or days. In previous interviews, Kythreotis and Fineberg offer many sources of inspiration that played a part in arriving at the current style. Star Wars designs are mentioned (especially the desert environments), Moebius’ comics and concept work, and Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild are all credited for the inspiration they provide. But apart from pop-cultural references, cues from academic disciplines like literature, cultural anthropology, and architecture get mentions too. Kythreotis and Fineberg are lifelong friends, and were raised on the same diet of video games and literature when they grew up, extending their interests well into their university years - Kythreotis studied architecture, Fineberg English Literature.

Sense of place

Reflecting on architecture, Kythreotis believes his designs benefit from his studies, but also the other way around: “Games really concern themselves with visual representation and a sense of place and time, things that architecture struggles with sometimes. You know, representing how people live and interact in an environment. Next to this I think something may be gained by architects by looking how the best game designers use the environment to teach players the rules of the game and use subtle cues to ensure they always know where to head to next. Both of these things could be applied to moving through and interacting with architecture, particularly public spaces.”

Asked about his current influences from architecture, Kythreotis mentions Carlo Scarpa, but also Alvaro Siza, John Sloane, Archigram, and Japanese Metabolism. “But don’t take this too literally”, Fineberg adds. “We take cues from everywhere. Literature plays a role too. The book I thought the most of during this project is probably Always Coming Home by Ursula Le Guin. It’s about the people who live in California several thousand years in the future, and it draws very heavily from Native American culture. It’s just about the people and their history, it’s got bits of poetry in it, songs, stories, and I like the idea that the work is just an exploration of a people.”

Star Wars

‘Not coming from games’ may help explain why the work of the duo feels different from that of others who try their hands at futuristic exploration games: it is suggestive of a world that runs a little deeper than what meets the eye. Kythreotis: “Science-fiction obviously features very heavily in popular culture - particularly mainstream cinema - but it’s often just about cool-looking technology and galaxy-saving heroes. We do have cool-looking technology - we’re big Star Wars fans! - but we want to tell a more grounded story about the people in the game’s world and how they live their everyday lives, so I think it’s good to get away from Star Wars and Marvel sometimes. Videogames can fall into the trap of being a little too self-referential and insular, and we wanted to avoid that by tapping into our strengths in terms of what we had studied prior to starting Shedworks.”